The cultural life in the south of Iceland is rich and diverse. There are art exhibits year round and various concerts featuring all types of music and groups are also frequent. Most towns have an amateur theatre with at least one production per year. Choirs are an integral part of Icelandic culture and about one in three inhabitants is or has been an active choir member. Folk dance groups, card playing and chess clubs, poetry reading groups and libraries play an important part in daily life.

Museums

South Iceland has all kinds of museums. Most are pretty standard, but others are dedicated to more abstract things, such as ghosts and other curious phenomena.

View

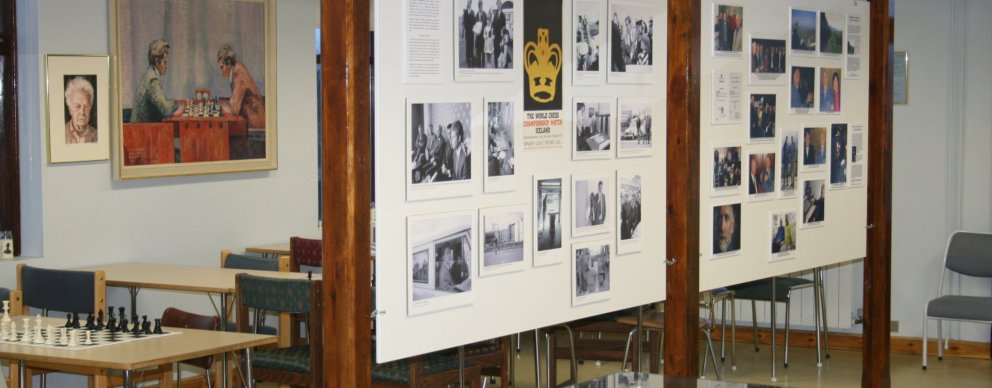

Exhibitions & Gallery

There is no shortage of different kinds of exhibitions all over the country. They are dedicated to anything from toys to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Art exhibitions also vary greatly and may be found in all sorts of places.

View

Cultural Centres

Hosting cultural events and educational programs for people of all ages. Cultural centers are located in most parts of the country.

View

Visitor Centres

Located at most of the more important and more popular nature sites, museums, and cultural establishments, visitor centers provide information and the chance to purchase souvenirs.

View

Crafts & Design

All types of craft and design have become popular all over the country. The variety is quite remarkable, and it´s safe to say that the local´s creative spirit is very active. Craft and design products are sold at select markets, specialty stores, or via the artists’ websites.

View

The Culture Map of South Iceland

The southern part of Iceland is rich in history, art and cultural events. In the local museums and exhibitions you can find information on volcanoes, glaciers and the Icelandic biological diversity, literature and poets, Icelandic seafarers‘ history and marine biology, fishing, chess, rocks, and moss, in addition to the diverse history of various towns and villages in South Iceland. Learn about environmentally friendly hydro-power plants, the practical use of geothermal energy, and get familiar with what it is like to live in a geo-thermally active area. Explore local art, architecture, or maybe drop by the last cave-dwellers of Iceland.

The Culture Map of South Iceland contains an image of South Iceland and useful information about local museums and exhibitions. You can get the culture map at the local museums and exhibitions.

View

The Icelandic Horse

Many horse lovers are particularly fond of the Icelandic horse and its attraction is such that a few erstwhile tourists have decided to establish residence here, some permanently, to pursue their interest in and dedication to this unique breed. Small herds were first brought to Iceland by the first settlers from Norway some thousand years ago. No more horses from foreign parts have been allowed on the island since that time, resulting in a truly Icelandic horse. The Icelandic horse is even tempered and hardy and renowned for its ability to master diverse gaits, notably the famous tolt. The Icelandic horse has always been a part of the culture and well into the previous century, an integral part of the workforce, utilized for transport and as a pack and draft animal. In the last few decades however, it´s primarily used for breeding and many own the horses merely for the sheer pleasure of caring for and riding such a fine specimen. There are several horse farms open to visitors and horses are available for rental through various agencies.

View

Icelandic Sagas in the South

Njáls saga

Southern Iceland is not the setting for many of the Icelandic sagas but one of the most famous, and certainly the longest, does take place in Southern Iceland and many places in the region are named in it. This is Njáls saga, “the Story of Burnt Njáll,” named after the chieftain Njáll Þorgeirsson from Bergþórshvoll in the Landeyjar district. The saga takes place from 950 to 1020 and is a tale of love, fate, fighting and vengeance. The story has a rich cast of protagonists and the character depictions are considered highly perceptive.

The Saga Centre

The Saga Centre in Hvolsvöllur is chiefly devoted to Njáls saga, which is understandable given that the surrounding area is the main setting for this most famous Icelandic saga. Visitors to the Saga Centre can view exhibitions on Njáls saga, Gallerý Orm, a local heritage museum and the latest addition to the centre, a 90-metre long tapestry depicting scenes from Njáls saga.

Other sagas

The Saga of the People of Flói begins in Norway and continues among settlers in the Flói district, particularly Stokkseyri and Gaulverjabær. It is best known for its vivid description of the voyage by the main character, Þorsteinn Örrabeinsstjúpur, to Greenland. The Saga of Gunnar, the Fool of Keldugnúp is named after Keldunúpur in the Síða district of Southern Iceland and part of the saga takes place there. Some of the action in the Saga of Hörður and the People of Hólm takes place at Grafningur near Þingvallavatn. Although the Saga of Grettir the Strong mostly takes place in Northern and Western Iceland, Southern Iceland does feature in this popular tale. Grettir spent several years hiding in the valley of Þórisdalur between the two ice caps Þórisjökull and Langjökull.

View

The Icelandic Turfhouse

Longhouses

The oldest type of dwellings in Iceland were longhouses which had one or two doors near the gable on the front of the house. In the 11th century the longhouses expanded so that there were three main buildings: a kitchen, living quarters and a store room and the other buildings could only be entered via the kitchen. In 1939 the remains of this kind of house were found at Stöng in Þjórsárdalur. The farm was destroyed in the eruption of Hekla in 1104. The Saga Age figure Gaukur Trandilsson lived at Stöng. To commemorate the 1100th anniversary of the settlement of Iceland, a replica farm based on the farm at Stöng was built in Þjórsárdalur in 1974.

The traditional turf farm

The Icelandic turf house developed from the longhouse in the 14th century. As the name indicates, the main building material is turf. Timber was used to build a frame and also panelling inside, while turf was used to form the roof and walls. Sometimes rocks were used in the walls with turf and stone slabs were sometimes used in the roof. In the late 18th century a new style of turf housing emerged, known as burstabær, which had wooden gables.

Building material

The Icelandic turf farm evolved from the longhouse, which came with the first settlers to Iceland. The main building material was in fact soil, both in turf and stone walls. Soil was packed tightly between the rocks and served both as an insulator and supported the weight of the walls. This type of housing did not last long and farmhouses needed to be frequently rebuilt.

Turf farms in Southern Iceland

A number of well-preserved turf farms and two turf churches can be found in Southern Iceland, including Austur-Meðalholt in the Flói district, Keldur in the Rangárvellir district and the turf farm at the outdoor museum at Skógar. The two churches are the chapel at Núpsstaður and the church at Hof in the Öræfi district. Most of these buildings are under the care of the National Museum of Iceland or other museums. Farm buildings made of turf and rock can be found widely across Southern Iceland in varying states of repair, some still in use. Replica turf houses have been built at Skálholt and Herjólfsdalur on the island of Heimaey.

View

History of fishing in South Iceland

Fishing from the glacial sands

The south coast of Iceland has virtually no harbours. Poor harbours are located at Eyrarbakki and Stokkseyri but there is nothing else on the mainland until you reach Höfn í Hornafirði. The island of Heimaey in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago on the other hand has an excellent harbour and for centuries has been the most important centre of fishing in Southern Iceland. Þorlákshöfn has also long been used by fishermen.

Over the centuries this harbourless coast has become the final resting place of numerous ships, both foreign and Icelandic. A port for the ferry to the Vestmannaeyjar was opened in 2010. Its location means that it regularly experiences problems due to the amount of sand accumulating in the harbour. At the beginning a large proportion of this sand was due to sediment brought down to the sea by the river Markarfljót following the Eyjafjallajökull eruption, which happened the same year as the harbour was opened.

In open rowing boats on the surf-beaten shore

In the past it was common to fish from open rowing boats along the south coast, particularly in the Mýrdalur and Eyjafjöll districts. Fishing was a vital part of the local economy and the main salvation in times of hardship. This type of fishing has long since ceased as it was highly perilous and many boats and lives were lost in the heavy surf when coming ashore or entering the sea on the harbourless coast.

The fishing station at Þorlákshöfn

Þorlákshöfn was a typical fishing station, attracting farmers and workers from other parts of the country during the fishing season, often the winter fishing season which lasted from 2 February to 11 May. Þorlákshöfn possesses an excellent natural harbour and is close to rich fishing grounds. In the period when rowing boats were used it was not uncommon for 30-40 boats to be fishing from Þorlákshöfn, meaning that 300-400 people lived in the fishing station over the season, living in dwellings made of stone and turf. People brought food with them from home. This way of life tested the fishermen both physically and mentally and they entertained themselves on land by playing games, reciting poetry and telling stories.

View

The emergence of towns and villages

Skálholt – a religious and cultural centre

Skálholt became an episcopal see in 1056 and became the nation’s main settlement, an honour it shared with Bessastaðir. Reykjavík was granted trading rights in 1786, but it was the establishment of Iceland’s first limited company around 1750 which laid the foundations for the development of a town. After a large earthquake in Southern Iceland in 1784, the episcopal see and the Latin school in Skálholt were closed and moved to Reykjavík several years later.

The growth of other villages

In the Middle Ages, when Skálholt was Iceland’s main settlement, Eyrarbakki was its main port. However, a village did not began to develop in Eyrarbakki, or indeed elsewhere in Iceland, until the 19th century. Eyrarbakki had its heyday from the mid-19th century until the first few decades of the 20th century. Eyrarbakki was one of the largest farms in Iceland and was in fact much bigger than Reykjavík, and for a time it appeared that it might become Iceland’s capital.

Around the same time, a village began to develop at Stokkseyri and soon afterwards at Vík í Mýrdal and Höfn í Hornafirði, and in mid-century Þorlákshöfn. Journalist Árni Óla called Þykkvabær a thousand year old country village and it is probably one of the oldest villages in the country. Vestmannaeyjar was granted trading rights at the same time as Reykjavík, 1786.

View

Artists from South Iceland

Many famous Icelandic artists come from Southern Iceland, including painter Jóhannes S. Kjarval, who was born at Efri-Ey in Meðalland, writer Þórbergur Þórðarson, born at Hali in Suðursveit, composer and cathedral organist Páll Ísólfsson, born at Símonarhús in Stokkseyri, painter Ásgrímur Jónsson, born at Rútsstaðir in Flói, sculptor Sigurjón Ólafsson, born at Eyrarbakki, sculptor Nína Sæmundsson, born in Fljótshlíð, sculptor Einar Jónsson, born at Galtafell in Hrunamannahreppur and painter Júlíana Sveinsdóttir, born in Vestmannaeyjar. The artist Erró grew up in Kirkjubæjarklaustur.

Hveragerði – the town of artists

When Hveragerði was developing, it was a popular spot for writers, composers, painters and other artists. It was home to writers such as Gunnar Benediktsson, Helgi Sveinsson, Jóhannes úr Kötlum, Kristján frá Djúpalæk, Kristmann Guðmundsson and Valdís Halldórsdóttir, artists such as Gunnlaugur Scheving, Ríkarður Jónsson, Höskuldur Björnsson and Kristinn Pétursson and the composer Ingunn Bjarnadóttir.

The artists mainly settled in three streets in the west of the village: Laufskógar was the street where the composers lived, Frumskógar was the street of the poets and the artists based themselves in Bláskógar. You can find out information on these artists at the places they lived and in the town’s park.

View